It’s that time again! Jane is off to her primary care provider for a regular checkup.

“Good to see you again, Jane.”

“Hi doc!”

“Everything looked good on your labs… except…”

“Except what?”

“Your liver enzymes are up again.”

“Again?”

“Yeah, you didn’t forget did you? The last test we ran showed this.”

“Really?”

“Yes. Are you taking any new medications?”

“No.”

“Drinking more than usual?”

“Nope! I promise!”

“Any herbs or supplements you’re taking?”

“I use a few capsules of lemon balm a few times a month…”

“Any fever or chills?”

“No.”

“Abdominal pain?”

“Nope.”

“Any weight change? Actually, you look a lot leaner. What have you been doing?”

“Yes. I’ve been lifting weights the last year consistently. And I’ve been doing cross fit. I just had a competition a few weeks ago.”

“Hmm. Anything else? Any dietary changes?

“Nope.”

“Travel?”

“No.”

“Okay, well I’d like to refer you to my friend down the street for further investigation.”

“Is there something wrong with me, should I be concerned?”

“I’m concerned about this. The gal I’m referring you to is a gastroenterologist. She’ll figure it out.”

Did doc miss anything? He might have. And now Jane is concerned and will be seeing a specialist, who will likely find nothing.

A little of my own story!

I actually ran into this issue with my physician during my early undergraduate years. I would get my blood draw a week after our cross-country training camp every August. My ALT and AST would be elevated, while nothing else was flagged. Doc never asked about exercise. He chalked it up to me being a rowdy college kid. The reality was I hardly ever drank and I never used recreational drugs (boring, I know)! He suggested further investigation, which I actually never followed up on, because at that age you think you’re invincible. But the point is I was a well trained athlete with about 6 years of running under my belt by this time experiencing this lab abnormality in response to training.

Diagnostic “oopsies”

Diagnostic errors have been estimated to occur about 12 million times a year. The Institute of Medicine has come to the conclusion that 1 in 20 individuals will experience a diagnostic error in their lifetime. A pretty big chunk of these errors comes from misinterpreting lab tests. Among the many consequences are harm to the patient, wasted time and resources.

In the case above, doc missed asking Jane more specifics about her exercise program. Had he questioned her, he would have found out that she had a big crossfit competition a few days before her most recent blood draw. This likely explains the abnormality of her blood test.

Exercise can raise flags on your lab tests

Words from gastroenterologist, Mary Sjogren, MD.

“Some physicians, whether they are gastroenterol-ogists or internists, forget that exercise can cause this abnormality. I have received referrals in the liver-disease clinic for a perfectly healthy person who happens to be exercising, whose history has not been taken or is not believed by the physician. This referral can lead to resources wasted on patients who have no illness and no other symptoms beyond these raised transaminase levels.”

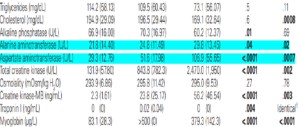

Jane’s lab results showed an increase in liver enzymes, which appear on a blood test your physician might run called a comprehensive metabolic profile. ALT and AST are transaminases, which your liver uses in part to make glucose to fuel your activity. We use them in medicine to assess liver health.

A desired result of exercise is damage to your tissues. This has to occur in order for the benefit of exercise to be expressed. A consequence of this damage is the leakage of these enzymes from liver and muscle tissue. If measured within a certain timeframe following the sufficient exercise stimulus, they will appear elevated on a blood test.

What is that timeframe?

Things get a little muddy here. Intensity, duration, how fit you are, the type of activity, whether you’re over or under trained can all widen and narrow this timeframe. The other thing is that the studies out there are not designed the same way. What would be most useful to us is an assessment of liver enzymes at several different timepoints following exercise in different contexts consisting of the factors above.

What’s been done?

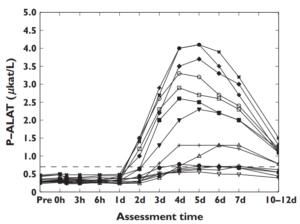

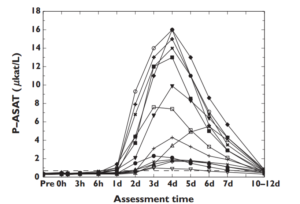

Peterson and friends subjected untrained males to one hour of fully body resistance training. 24 hours after training, ALT and AST began to increase sharply, peaked between 4-6 days, and returned to baseline 10-12 days after that single exercise session. You can see this pretty clearly in the graphic below.

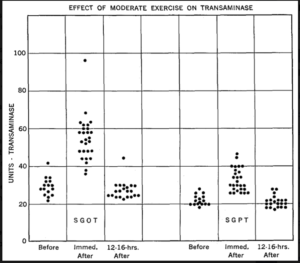

In another study looking at trained military personnel, levels increased anywhere from two to nearly five fold immediately post exercise. But returned to baseline within 12-16 hours.

In marathon runners, investigators measured liver enzymes at two different time points following completion of the event. On average, AST levels were increased 4 hours post, and further increased 24 hours post marathon.

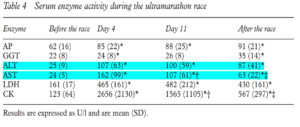

In ultra endurance athletes, AST and ALT increased 4-6 fold 4 days into an ultra marathon. Measurements taken within 30 minutes after crossing the finish line showed persistence in enzyme elevation.

What you need to know

You need to be aware that exercise has the capacity to raise your liver enzymes. I would not put much emphasis on how fit you are. The reason for this is that regardless of your training status, you have the capacity to rock the boat at anytime.

Say you take a week or two off. Or perhaps you decide to increase your exercise frequency. Maybe you switch up your workout in some way, you go do sprints when you normally do weights, or join a friend for spin class at Orange Theory when you normally do not. It could just be a bad week, with final exams, taxes, a bug going around, or whatever else might be an added stress. The scenarios that predispose to this response are legion.

That being said, when you have your labs done, be mindful of any changes in your recent exercise program. Chances are your doctor might miss it.

The effects of exercise on routine lab metrics actually extends beyond just liver enzymes. We can see alterations in several different parameters acutely and chronically. Some of this I’ll cover for you in the future.

Questions to ask

Did I exercise within a few days of the blood draw?

If yes, then…

Was the stimulus I experienced novel? Was it new to me?

Was my exercise duration longer than usual?

Was my exercise intensity greater than usual?

Did I perceive my most recent bout of exercise to be difficult?

If you answer yes to the first question AND to any of the other questions you might consider a transient response to exercise as a potential explanation!

Further Reading

Singh, Hardeep, Ashley ND Meyer, and Eric J. Thomas. “The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations.” BMJ quality & safety (2014): bmjqs-2013

Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007 Dec; 3(12): 913–914.

Pettersson, Jonas, et al. “Muscular exercise can cause highly pathological liver function tests in healthy men.” British journal of clinical pharmacology 65.2 (2008): 253-259

Schlang, H. A. “The effect of physical exercise on serum transaminase.” The American journal of the medical sciences 242 (1961): 338

Kratz, Alexander, et al. “Effect of marathon running on hematologic and biochemical laboratory parameters, including cardiac markers.” American journal of clinical pathology 118.6 (2002): 856-863

Fallon, K. E., et al. “The biochemistry of runners in a 1600 km ultramarathon.” British journal of sports medicine 33.4 (1999): 264-269

Foran, Stacy E., Kent B. Lewandrowski, and Alexander Kratz. “Effects of exercise on laboratory test results.” Laboratory medicine 34.10 (2003): 736-742

Photo credit: Health.usnews.com